Finding Our Voices

![]()

With heartfelt thanks to our advertisers

Comprehensive Eye Examinations, Contact Lens Fittings, Lasik/Cataract Co-management. Located within the Optical shop of Massachusetts Opticians. Offering top quality eye-wear, service and repair.

![]()

Littleton, MA 01460

978-501-2222

smile@zubidental.com

www.zubidental.com

Program Notes

Friday, October 18, Chelmsford Center for the Arts, 7:30 p.m.

Introduction: We’re here to introduce you to a new way of thinking about the Symphony Orchestra. Commonwealth Orchestra is here to increase awareness of the wealth of American-born orchestral music that is beautiful and diverse … music that represents the heritage and the musical traditions that have grown from the people of this country.

We embrace the European antecedents of the symphony orchestra as a building block to great art music. However, our primary mission is to create an orchestra that has a unique American orchestral voice that hearkens back to the many voices of generations of schooled and folk musicians who came to this country as strangers and sang the truth of their experiences.

Our purpose this afternoon is to demonstrate our idea of what an American symphony orchestra should look and sound like. Combining the tropes of an old-fashioned variety show with stories and poems and a bit of humor along with some classical music that we musicians really like, we hope that you, dear audience, will catch our love of a Home Grown Symphony Orchestra.

Music: Opening Theme. O Blundering Dervish, by Charles Turner

Tomoko Iwamoto is a violinist, arranger and composer. She started playing the violin at the age of six in Osaka, Japan. She played the saxophone and sang in a commercial band while pursuing engineering studies in college. After moving to the US to attend Berklee College of Music, she performed with the classical ensembles including, Lexington Symphony Orchestra, New England Philharmonic, Avalon String Quartet, Gliere String Duo, and the Clef Club Syncopators, and with jazz and Latin ensembles including A la Modal, Hypnotic Clambake, RumboSur, and Greater Bostonians. Tomoko holds a BA from Berklee and a BS from Keio University. She currently teaches on the faculty at Brookline Music School and leads a double life as a software localization specialist. Tomoko arranges and composes for J-Way, Mood Swings Orchestra, and Newton All-City Orchestra and now for Commonwealth Orchestra Outreach Project. Her gypsy jazz string quartet, 440, released their first album “Why Why” in November 2017. She is currently working on a second album “Yo-ki Swing” for October 2019 release. You can visit her website at ww.jazzyviolinist.com

Music: Exuberance, by Tomoko Iwamoto.

In Tomoko’s voice for her transcendent piece:

Exuberance is about joy and energy of life. We would all have sad moments from time to time, and struggle with difficulties sometimes, but after the end of the day, we welcome a new day with hope, ambitions, inspirations and excitement.

Open the door and come out of your small nest, get out and jump into the bright blue sunny sky, that’s what I imagine from Exuberance!

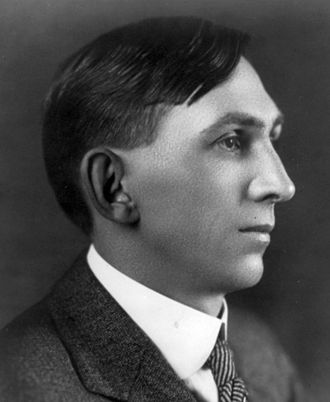

Charles Wakefield Cadman (1881-1946) is one of those composers who wrote prolifically but got stuck with a single “hit”. He grew up a small town boy — in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, he probably did all the things boys did in those days: played sandlot baseball, turned over rocks, swam in the swimmin’ hole, and went to school. He didn’t take piano lessons, though, until he was 13 and only because he was building instruments out of available materials — rubber bands and a pillbox sufficed. Once started, he excelled, but his was a humble schooling. He never went off to the great Conservatories of Europe; he paid for his lessons with the conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra on piano, in theory and orchestration out of his pocket on a pay-as-you-go basis out of his earnings as a railroad clerk until he was 18.

Cadman, however, was no bumpkin. He was keenly interested in the indigenous music of American Indians, and established himself as a writer and authority on Native American music, as well as an adept composer using the melodic motives of the Omaha Indians as the ground source of his songs and orchestral works — material that he collected by living among the Omahas and recording their music on wax cylinder. We don’t know if he was influenced by similar work in England by Percy Grainger and Gustav Holst, but his work is co-incidental with theirs so knowledge is a distinct possibility on the part of Cadman. In any event, Cadman established his career on the basis of Indigenous and Folk music and ended up with an output of 300 songs, 10 operas, ten symphonic works and a host of chamber and incidental music, including a couple film scores. His “hit”? From the Land of Sky Blue Water (having nothing to do with a beer commercial). We promise we’ll try to see this wonderful composer better represented for you.

Music: American Suite, by Charles Wakefield Cadman

I: Indian

The Voice

by William Oandasan

“first there is the word and the word is the song”

1

song gives birth to

the song and dance

as the dance steps

the story speaks

2

the icy mountain water

that pierces the deep thirst

drums my fire

drums my medicine pouch

3

deep within my blood

a feather in the sky

foam on clear water

Tayko-mol!

4

free as the bear

and tall as redwoods

throb my blood roots

when spirits ride high

5

a valley ripe with acorns

and yellow poppies everywhere

as i stand here

dreaming of you

6

jolting my dream

an old man struggling

with an eel … his coat appears

disheveled and empty

7

in a sacred manner

i sang and waited

a lick of your blood

i must take, reverently, deer

8

for you, blue corn baby,

my thoughts

on a melody of love

sail the sky

9

around fire on my head

a rattlesnake hisses and slithers

then flies up out of sight

fighting in sleep i cry out

10

the snake in my spine is tensing

for combat

thoughts become forced and tight

the air is a sharp knife

11

from under me today

the earth was pulled

balancing on a sharp mountain ridge

i search for a plain

12

Tayko-mol has not left us

but lives in the pulse

of our words, and waits

in the azure for us all

William Oandasan was a member of the California Yuki tribe. He was an advocate for Native American writers and the author of a number of collections of poetry. He died in 1992.

II. Negro

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

by Paul Laurence Dunbar

I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,

When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore,

When he beats his bars and would be free;

It is not a carol of joy or glee,

But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core,

But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings –

I know why the caged bird sings.

III. Old Fiddler

The Monosyllable

by Josephine Jacobsen

One day

she fell

in love with its

heft and speed.

Tough, lean,

fast as light

slow

as a cloud,

It took care of

of rain, short

noon, long dark.

It had rough kin;

did not stall.

With it, she said,

I may,

if I can,

sleep; since I must,

die.

Some say,

rise.

![]()

Charles Turner (b. 1951) began composing in high school. He has degrees in voice performance and composition at the University of Iowa and U Mass Amherst, where his composition teachers included Richard Hervig, William Hibbard, Peter Tod Lewis, Donald Jenni, Robert Stern, and Charles Fussell.

Charles is music director at Second Congregational Church in Beverly, and is a board member of the Triad Choral Collective, in which he also sings and conducts. His choral music has been performed in the Boston area by Tapestry, Church of the Advent Choir, Capella Alamire, Polhymnia Choral Society, Musica Sacra, Canticum Novum of Worcester, and Triad. His opera Paper Or Plastic was premiered in June, 2013 in Boston’s Outside the Box Festival. His piece ‘Bartok Variants’ was performed recently by the Gordon College Concert Band, and his cello-and-piano piece ‘Shipwreck Dreams’ has been recorded by cellist Marshunda Smith. Charles plays doublebass in several North Shore orchestras.

In Turner’s words:

‘The White Pilgrim’ is an instrumental fantasy based on a song of the same title which I wrote a few years ago for myself to sing. The song is written as a pseudo-19th-century ballad. It is very mournful and has an oddly unfinished quality which I like very much.

The instrumental version retains the mournfulness and some of the strangeness of

the text, I think. I wrote the piece for the Commonwealth Orchestra Outreach Project at the suggestion of its music director, Lucinda Ellert. I am grateful for Lucinda’s encouragement.

Music: The White Pilgrim, by Charles Turner

“I came to the spot where the white pilgrim lay,

And pensively stood by his tomb;

When in a low whisper I heard something say—

How sweetly I sleep here alone.”

The tempest may howl, and the loud thunders roll,

And gathering storms may arise;

Yet calm are my feelings, at rest is my soul,

The tears are all wiped from my eyes.

The cause of my master propelled me from home,

I bade my companion farewell,

I left my sweet children, who for me now mourn,

In far distant regions to dwell.

I wandered an exile and stranger below

To publish salvation abroad;

The trump of the gospel endeavored to blow,

Inviting poor sinners to God.

But when among strangers, and far from my home

No kindred or relative nigh,

I met the contagion and sunk in the tomb—

My spirit to mansions on high.

O tell my companion and children most dear

To weep not for Joseph, though gone;

The same hand that led me through scenes dark and drear,

Has kindly conducted me home

![]()

Music: Dramatic Tension No. 36, by Julián Andino

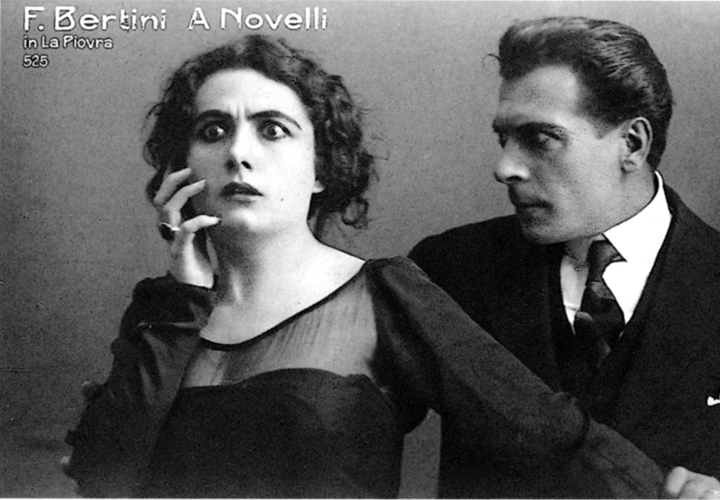

Wikipedia defines a silent film as film with no synchronized recorded sound (and in particular, no audible dialogue). In the early days of film, when the technology was not advanced enough to accommodate a sound track, plot was conveyed by the use of title cards, but in fact the term “silent film” is a bit inaccurate, because these films were almost always accompanied by live sounds. Quoting Wikipedia: “a pianist, theater organist—or even, in large cities, a small orchestra—would often play music to accompany the films. Pianists and organists would play either from sheet music, or improvisation. Sometimes a person would even narrate the inter-title cards for the audience.”

We have taken this “voice” – for the actors and actresses of the day spoke volumes with their broadly overacted expressionism – and brought it up to date for you. Fans of silent film know that the action in the movie was almost completely sufficient to make the story understandable and the title cards mostly clarified rather than explicated the plot. Our concept is that the “title cards” as seen in the power-point presentation is the plot, and you’ll have to imagine our hapless couple trying to make themselves understood to one another in an alternate world where speech is always seen but never heard.

‘Dramatic Tension No. 36’ provides the backdrop for our domestic train-wreck. The composer and violinist Julián Andino (1845-1926) was of Afro-Cuban descent, born in Puerto Rico and later moved to New York and established himself as a composer of snip and paste music for film and theatrics. Anyone who has looked through collections of old printed stock arrangements for small orchestra has come across these oddly-titled pieces. They all have a rather static character, because they were never composed to be played as anything other than background music to some kind of action. And yet, composers like Andino knew their stuff – Maud Cuney-Hare wrote in Negro Musicians and their Music (1933, one of the few available mentions of Andino) that he was clearly trained and not a folk musician. More on that later, but you’ll hear structure and development in Dramatic Tension No. 36 that makes it solidly written and underscores a dramatic scene beautifully, if not somewhat overblown.

![]()

New Orleans in the mid-1800’s could accurately be described as not so much a hotbed of musical genre but more a microbrewery of pure ingredients, fermented into a rich, sweet, tart intoxicating ale. Louis Moreau Gottschalk was the city’s most celebrated composer before the Civil War, his piano works deftly borrowing from the Afro-Cuban, Creole, Mexican and Puerto Rican sources which resulted from the trade and constant immigration and movement between those countries and the Louisiana coastal city.

Early in the century, the different genres of music were more individuated and localized, and Danzón, a particularly cross-inseminated import from Cuba and Puerto Rico was a popular form of music for socializing and dancing in the Latin Quarter. The exact roots of danza puertorriqueña has been much studied in enthnomusicological circles, but whereas the exact manner in which the forms of danza were borrowed between the two islands is unknow. Nevertheless it is understood that the influence of art music from Spain by composers such as Antonio Soler or Mateo Albéniz upon the two islands became essentially two halves of the same clamshell.

Here’s where things get interesting, though. Danzón, as a pre-Civil War musical form is unique to the times, and deeply influenced by the culture of New Orleans. As a form, it has some very interesting characteristics and it seems to have been largely influenced and standardized by composer, Julian Andino, our composer of silent film music. As one historian notes:

Julián Andino (1845-1926) employed the combination of duple-triple rhythms in the accompaniment [of danza]. The concept of the tresillo elástico (elastic triplet) implied that the conventionally known triplet in the bass figuration was not to be played as such, but as a syncopated rhythm with uneven, nearly swung note values.

While danza is a fairly simple form in which melody is prominent over an elegant accompaniment, it attains heights of complexity with rhythmic drive, abrupt changes in mood and character, and clear references back to the culture that inspired the music. In short danza was literally home away from home for the transplantees of New Orleans.

Now back to Gottschalk, the mixed-race creole composer whose music made such a deep mark on American culture. Before the Civil War (Gottschalk died in 1864), the composer made a number of lengthy visits to Hispanola and Cuba, and his music during that later period in his life clearly reflected that culture. What he brought back to audiences in New Orleans bridged the gap between the culturally inflected social music of the Latin Quarter and art music of the concert hall. The result was the start of publishing these widely disseminated danza forms, thus providing a record that heretofore hadn’t existed.

Later, published sheet music was analyzed by ethnomusicologists and the forms were named and codified. Julián Andino’s tresillo elástico was analyzed as “terno-binario” (indicating three-against-two polyrhythms) and the importance of danza became historical record. But another aspect is equally critical: there is a clear relationship to African-American music and the evolutionary pathway to the American Jazz that would arise in 50 years or so.

The two little Cuban danzon, “Anita” and “¡Por Ti!” were written by New Orleans-based Spanish-born composer Carlos Maduell (1836-1900) and published by Louis Grunewald in 1883. Except for this publication and a subsequent piece, almost nothing is known about him. I was inspired by these two simple tunes to explore the inherent “terno-binario” tensions against modern compositional techniques and set it for our chamber ensemble.

The Rise of Danza Puertorriqueña, uncited article on https://pianodanza.com/the-rise-of-the-danza-puertoriquena/

Jack Stewart, Cuban Influences on New Orleans Music, The Jazz Archivist, Vol XIII, 1998-1999. https://jazz.tulane.edu/sites/default/files/jazz/docs/jazz_archivist/Jazz_Archivist_vol13_9798.pdf

Maud Cuney-Hare, Negro Musicians and their Music.

Alejandro L. Madrid, Robin D. Moore, Danzón: Circum-Caribbean Dialogues in Music and Dance. In Eurojazzland: Jazz and European Sources, Dynamics, and Contexts, edited by Luca Cerchiari, Laurent Cugny, Franz Kerschbaumer

Music: Los Bailes Cubanos, by Carlos Maduell (arr. Ellert)

Cultivo Una Rosa Blanca (Verso XXXIX)

by Jose Marti

Cultivo una rosa blanca

En julio como en enero,

Para el amigo sincero

Que me da su mano franca.

Y para el cruel que me arranca

El corazón con que vivo,

Cardo ni oruga cultivo:

Cultivo la rosa blanca.

Translation:

I have a white rose to tend

In July as in January;

I give it to the true friend

Who offers his frank hand to me.

And for the cruel one whose blows

Break the heart by which I live,

Thistle nor thorn do I give:

For him, too, I have a white rose.

![]()

Cape Cod based saxophonist and composer Bruce Abbott (b. 1955) has spent a lifetime resolving the two languages of jazz and classical — to find a lingua franca, as it were. In his own words:

It wasn’t until I began my college music studies that I truly became interested in trying to perform classical music. In my program at the University of Rhode Island I met other saxophonists who were interested in more than jazz and who inspired me to explore classical music. With jazz, if there’s something I can’t do, I just do something else. With classical music I don’t have that luxury. I have to perform the music as written and attempt to realize the composer’s intent. Yes, there’s lots of room for expression and myriad other personal choices, but ultimately I must be true to the notes on the page, to the composition. The precision and discipline which that requires build musical character.

I like to think that for all of us musicians, when we are working on a composed piece of music, it’s like we are exploring the mind of the composer. I’m sure it’s the same for actors and their relationship with scripts and playwrights. There are pieces I’ve been playing for 30 or more years and it seems that each time I play them I learn something new about what the composer is seeking. It’s as if each time I play a piece is the first time it’s been played. That intrigues and energizes me and hopefully the listener as well!

Music: Homage to Georgia O’Keeffe

“I found that I could say things with colour and shapes that I couldn’t say in any other way things that I had no words for,” Georgia O’Keeffe (November 15, 1887–March 6, 1986)

The inspiration for its title is found in two paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue and Green Music and Music, Pink and Blue, abstract works in which she tried to evoke the experience of sound.

I. Ballad in Blue and Green

II. Passacaglia in Pink and Blue

Finally, on the subject are a few words by Georgia O’Keeffe herself:

A flower is relatively small. Everyone has many associations with a flower — the idea of flowers. You put out your hand to touch the flower — lean forward to smell it — maybe touch it with your lips almost without thinking — or give it to someone to please them. Still — in a way — nobody sees a flower — really — it is so small — we haven’t time — and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. If I could paint the flower exactly as I see it no one would see what I see because I would paint it small like the flower is small.

So I said to myself — I’ll paint what I see — what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it — I will make even busy New-Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers

![]()

Florence Price (1887-1953), the music of her powerful voice initially stilled by indifference after her death, is currently enjoying new recognition for the beauty and gravitas of her compositional output. Her basic stats are thus: *born in Little Rock, Arkansas, *classmates with William Grant Still, *initially taught piano by her mother, *graduated high school at age 14 having already sold one piece of music (now lost), *went to New England Conservatory as a piano and organ major and graduated with honors at age 18, *went back to Little Rock to teach school — all this before 1910. Any chance at artistic legacy could have evaporated at that point, but violence against African Americans and deep racism in the south drove her to Chicago in 1927 where she got caught up in the westward bloom of the Harlem Renaissance and therein, found her voice.

At the apex of her career, her First Symphony was performed by the Chicago Symphony on June 15 1933, and subsequent rave reviews made her a darling among luminaries as Marian Anderson and Langston Hughes. She continued to have an active career, especially in Chicago for another 20 years until her death on June 3, 1953, at which time awareness of her work rapidly fell off until she became virtually obscure with the exception of some continued play in the Chicago area.

Her music does not fall into what became canon of the second half of the 20th century. After World War II compositional styles that were acceptable for study by young conservatory students followed either the 12-tone method pioneered by Schoenberg and the atonalism which was derived from the tension-fraught composers that came out of the turbulent war years. The music that was written by Price and her two fellow composers of color, William Dawson and William Grant Still, was often seen as quaint and old-fashioned, but the late-romanticism that uses the idioms and motives of her cultural traditions rings very strong to this day. From the article in Wikipedia:

Even though her training was steeped in European tradition, Price’s music consists of mostly the American idiom and reveals her Southern roots. She wrote with a vernacular style, using sounds and ideas that fit the reality of urban society. Being deeply religious, she frequently used the music of the African-American church as material for her arrangements. At the urging of her mentor George Whitefield Chadwick, Price began to incorporate elements of African-American spirituals, emphasizing the rhythm and syncopation of the spirituals rather than just using the text. Her melodies were blues-inspired and mixed with more traditional, European Romantic techniques. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Price

This review is doesn’t really do her justice; the quote below maybe gives a better idea of the depth of her understanding of the complexities of composition and her gaze into the black American soul:

Price seems never to have thought of herself as avoiding ethnic emphasis in her music … (H)er methods are actually quite close to Dvorak’s in the way she approaches the use of ethnic materials (both of the Old and the New Worlds), and she can certainly be aligned stylistically with (William) Dawson, who said that his aim was to “write a symphony in the Negro folk idiom .. in the same symphonic form used by composers of the romantic-nationalist school.” When Price’s third symphony was to be performed in Michigan by Walter Poole in 1940, she wrote of it: “It is intended to be Negroid in character and expression. In it no attempt, however, has been made to project Negro music solely in the purely traditional manner. None of the themes are adaptations or derivations of folk songs.” In this respect she did differ from Dawson, who used actual folk melodies in his symphony, but she certainly did not avoid ethnic emphasis in her music. (Florence Price, Composer by Barbara Garvey Jackson in The Black Perspective in Music Vol. 5, No. 1 (Spring, 1977)).

Three African American composers during the pre-war period successfully gained notice by white audiences: Florence Price, William Dawson and William Grant Still. This triumvirate long remained the sole exemplars of symphonic music that touch the soul of black Americans until recently but today their music is coming back with a vengeance and gaining new audience and new followers among the fresh voices of young composers. We are so fortunate that more of Price’s scores were discovered in Chicago in 2008, this little Quintet for Piano and Strings among those works, of which we are so pleased to present two movements.

Music: Quintet for Piano and Strings, by Florence B. Price

I. Allegro

II. Andante Cantabile

III. Allegretto

Still I Rise

by Maya Angelou

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

’Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

’Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

![]()

Charles Turner has written a delightful theme song/bumper for this concert. Of this quirky little piece he says: “Oh Blundering Dervish” was written as a sort of ‘curtain-raiser’ piece for the Commonwealth Orchestra Project. I wanted something jolly, fun, and energetic; something with an American flavor that dances. I reached back in time for syncopated dance music, but there is some rock flavor to it as well. Have fun!

Music: Reprise. Oh Blundering Dervish, by Charles Turner

Poem by Ruzica Matic

November 2015

I am an invisible woman

inside a circus tent

– a ghost of a clown

who lost her nose

fading into red

weighed down

by words unsaid

I am a clumsy dervish

whirling

a tumbling blur

forever restless

like a wild curl

I am a shadow

when need be

a wallflower

a hidden bower

protecting me

I am your mirror

your frown

your smile

I am your window

as you are mine

Program notes copyright (c) 2020, by Commonwealth Orchestra Outreach Project